Why the Viral Guacamole Storing Trick Is a Myth, According to Food Science

A popular guacamole storing trick—placing an avocado pit in the bowl—is a myth, according to food scientists. Browning is caused by oxidation from air exposure, not the pit's absence. Effective methods involve creating an airtight barrier with plastic wrap or water.

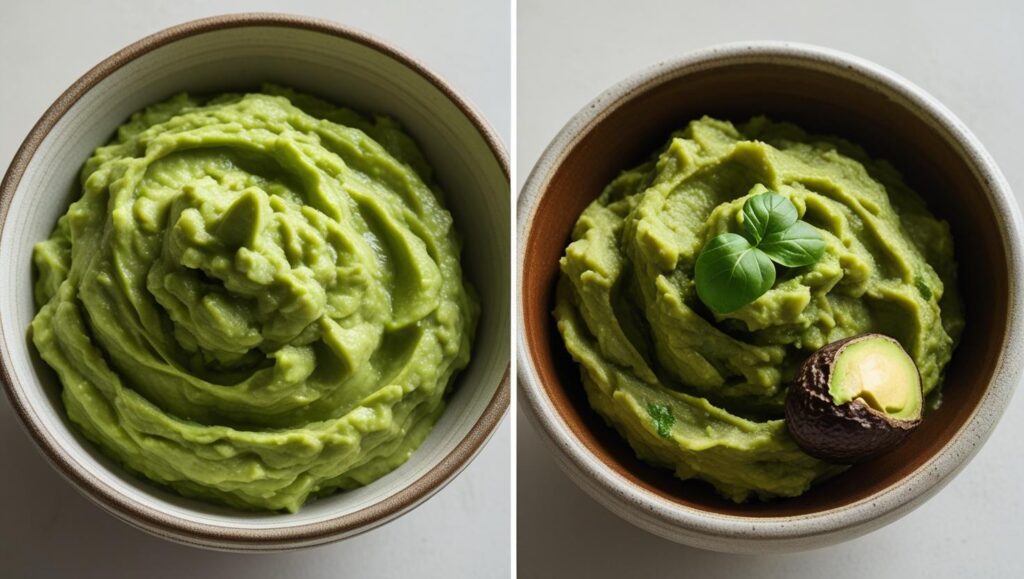

For years, home cooks have sworn by a popular guacamole storing trick: leaving the avocado pit in the bowl to prevent the dip from browning. However, food scientists confirm this is a persistent myth. The browning process is a chemical reaction with air, and the pit offers no special protection beyond the small area it physically covers.

The Enduring Myth: Why the Avocado Pit Fails

The advice is a staple of kitchen folklore, passed down through generations and shared widely on social media: to keep guacamole green, simply leave one or both of the avocado pits in the finished dip. The logic seems plausible, as the area directly beneath the pit often remains bright green while the surrounding surface turns a drab brown.

This observation, however, leads to a false conclusion. The pit isn’t releasing a magical enzyme-blocking compound. “There was nothing in the pit that I knew of that should have inhibited the enzyme, so it had to be the oxygen,” Dr. Karen Schaich, a food scientist at Rutgers University, explained to Inverse.

The reality is far simpler: the pit acts as a physical barrier, just like a rock or a spoon would. It only protects the portion of guacamole it is directly touching from exposure to air. The rest of the dip remains vulnerable to the inevitable chemical process of oxidation.

The Science of Browning: Understanding Enzymatic Oxidation

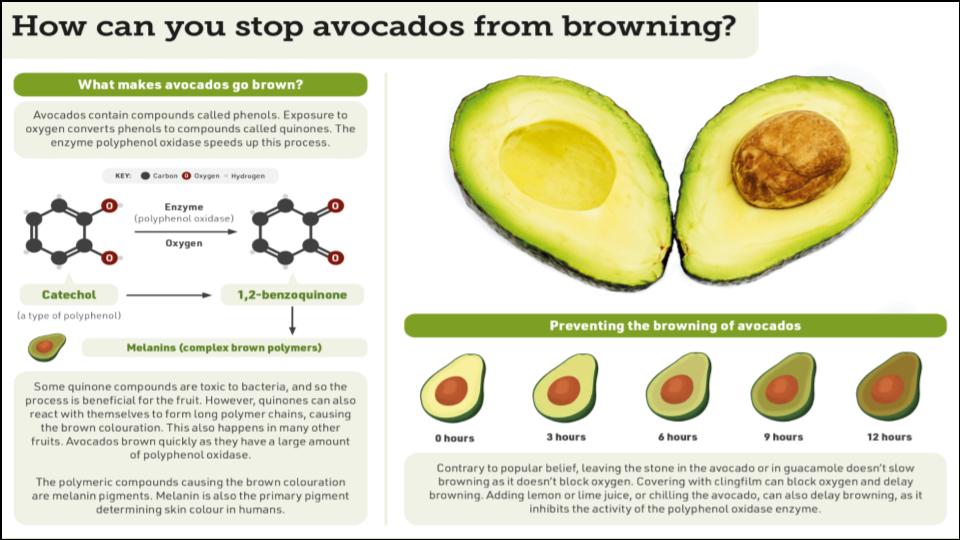

The browning of guacamole, apples, and potatoes is a natural process known as enzymatic browning. Avocados contain an enzyme called polyphenol oxidase (PPO). When the avocado’s cells are crushed or cut, the PPO is released and comes into contact with oxygen in the atmosphere.

This exposure triggers a chemical reaction, converting compounds called phenols into new molecules called quinones. These quinones then polymerize, or link together, to form the brown-colored pigments known as melanin.

“This is the same reaction that causes browning in many fruits and vegetables,” a guide from the Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST) explains. The key to preventing oxidation is to limit the enzyme’s access to oxygen or to alter the environment to make the enzyme less effective.

A Better Guacamole Storing Trick: Methods Backed by Science

While the avocado pit in guacamole method is a bust, food scientists and culinary experts agree on several effective techniques that directly combat oxidation.

The Physical Barrier Method

The most critical step is to block oxygen from reaching the surface of the dip.

According to food writer and expert J. Kenji López-Alt, a physical barrier is paramount. In his work for Serious Eats, he emphasizes that preventing air contact is the true solution. The most common and effective technique involves placing plastic wrap directly onto the surface of the guacamole.

“Press the plastic directly against the top of the guacamole and seal along the edges of the dish until it’s as air-tight as possible,” advises one culinary expert. This method minimizes the air pocket that would otherwise sit between the dip and a lid, starving the PPO enzyme of the oxygen it needs to function.

A related technique, tested and proven by publications like Real Simple and Food Republic, involves adding a thin layer of water. After smoothing the guacamole in an airtight container, gently add about a half-inch of lukewarm water on top to create a perfect seal. Because guacamole is high in fat, which is hydrophobic, the water will not be absorbed. Before serving, the water can be simply poured off.

The Acidity Solution

Another scientifically sound approach involves changing the pH of the guacamole. The PPO enzyme functions best within a specific pH range of 5.0 to 7.0. Adding a strong acid like lime or lemon juice lowers the pH, making the environment inhospitable for the enzyme and slowing the browning reaction.

The citric acid in the juice…retards the enzymatic activity of the polyphenol oxidase by lowering the pH, confirms a report from How Divine. Most guacamole recipes already call for lime juice for flavor, but an extra squeeze over the top surface before storage can provide additional protection.

Expert Consensus and Reducing Food Waste

The consensus among food scientists, including the late, renowned author Harold McGee (On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen), is that any claim of the pit’s special powers is unfounded. McGee famously demonstrated the myth by placing a pit in one bowl of guacamole and a pit-sized lightbulb in another; both browned at the same rate.

While using the ineffective guacamole storing trick is harmless, it contributes to food waste when people discard perfectly edible, albeit slightly discolored, dip. The brown layer is not a sign of spoilage, and the Hass Avocado Board notes it can simply be scraped off to reveal the green guacamole underneath, as long as the dip is no more than three days old.

Understanding the simple science of oxidation allows home cooks to store their guacamole effectively, ensuring it remains as vibrant and appealing as when it was first made. By focusing on limiting air exposure and using acidity, the problem of brown guacamole can be largely solved.

The Rise of ‘Avocado Hand’: How to Cut an Avocado Safely, According to Surgeons