For Heart Health, Experts Now Say Saturated Fat a Greater Concern Than Dietary Cholesterol

New research confirms that for most people, dietary cholesterol from foods like eggs does not significantly raise blood cholesterol. Health experts now identify saturated fat as the primary dietary culprit for poor heart health, shifting focus to overall dietary patterns.

For decades, the humble egg was a subject of intense nutritional debate, often banished from breakfast plates over fears of its impact on cholesterol. New and consolidating research, however, confirms a significant shift in scientific understanding: for the vast majority of people, dietary cholesterol consumed from foods like eggs has a minimal effect on blood cholesterol levels. Instead, health experts are pointing to a different culprit for poor heart health: saturated fat. This evolving consensus has reshaped national dietary guidelines and is prompting a re-evaluation of what constitutes a heart-healthy diet, focusing less on single nutrients and more on overall eating patterns.

Key Takeaways: Dietary vs. Blood Cholesterol

| Key Fact | Detail |

| Dietary vs. Blood Cholesterol | The cholesterol you eat (dietary) is distinct from the cholesterol in your bloodstream (blood), most of which your liver produces. |

| Primary Culprit Identified | Saturated and trans fats have a much greater impact on raising harmful LDL blood cholesterol than dietary cholesterol does. |

| Egg Consumption Guideline | Healthy individuals can typically enjoy up to one whole egg per day as part of a healthy diet without significant risk to heart health. |

The Shifting Science on Dietary Cholesterol

The long-held belief that eating cholesterol-rich foods directly leads to high blood cholesterol has been systematically challenged by modern research. The body, it turns out, has a sophisticated self-regulation system.

“For most people, the amount of cholesterol eaten has only a modest impact on the amount of cholesterol circulating in the blood,” explained Dr. Walter C. Willett, a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in a university publication. When you consume more cholesterol, your body typically produces less to compensate, a mechanism that maintains a relative balance.

This understanding was formally recognized when the 2015-2020 U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans removed the specific recommendation to limit cholesterol intake to 300 milligrams per day. The most recent 2020-2025 guidelines continue this approach, instead advising a focus on limiting foods high in saturated fat.

What Really Raises Blood Cholesterol?

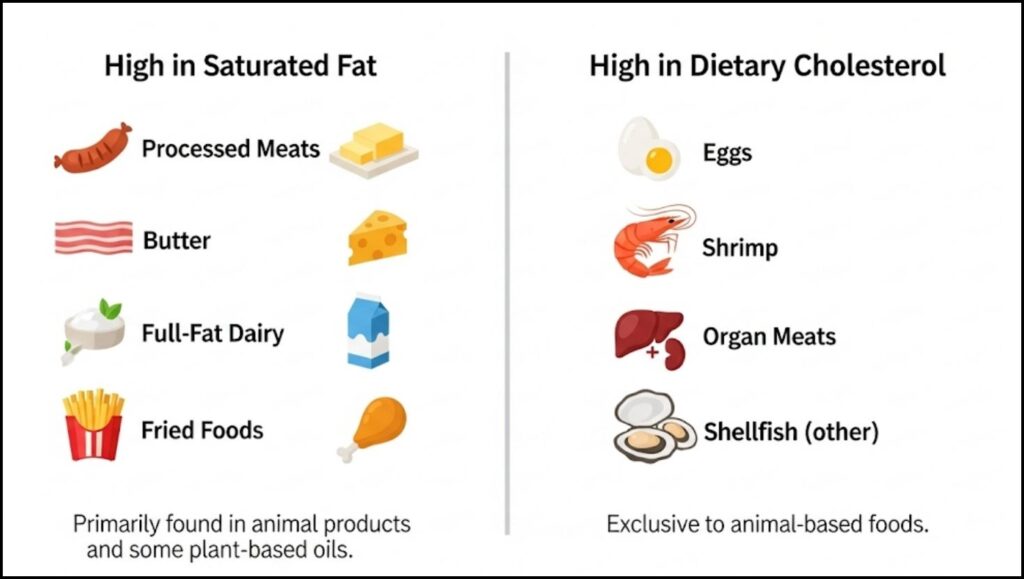

If dietary cholesterol isn’t the primary villain, what is? The scientific consensus points squarely at saturated and, to an even greater extent, trans fats.

Foods rich in these fats include:

- Red and processed meats (sausages, bacon)

- Full-fat dairy products (butter, cheese, cream)

- Baked goods and fried foods made with palm oil, coconut oil, or hydrogenated oils

“Saturated fats and trans fats prompt the liver to produce more LDL cholesterol, which is the ‘bad’ cholesterol that can build up in arteries and lead to heart disease,” states the American Heart Association (AHA). The AHA recommends that saturated fat should make up no more than 5-6% of total daily calories. For a 2,000-calorie diet, that translates to about 13 grams of saturated fat per day.

In contrast, a large egg contains about 186 milligrams of cholesterol but only about 1.6 grams of saturated fat, alongside valuable nutrients like high-quality protein, Vitamin D, and choline, which is crucial for brain health.

A Word of Caution for Some

While the green light for eggs applies to the general population, experts advise a more cautious approach for certain individuals. People with existing conditions like type 2 diabetes or established heart disease, or the small percentage of the population known as “hyper-responders” to dietary cholesterol, may need to be more mindful. “Individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or high LDL cholesterol should discuss their egg consumption with their physician or a registered dietitian,” advises the Cleveland Clinic. The key is personalized nutrition based on individual health status and risk factors.

The historical confusion arose because many foods high in dietary cholesterol—like fatty steaks and full-fat dairy products—are also high in the saturated fat that drives up blood cholesterol. Early studies often struggled to separate these two effects. Modern, more nuanced research has been able to isolate the variables, vindicating foods like eggs and shrimp that are high in cholesterol but not in saturated fat.

The ultimate takeaway from health organizations worldwide, including the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), is to focus on the bigger picture. “While we do need some cholesterol in our blood to stay healthy, it’s the ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol that you need to watch,” the NHS advises. “Eating a healthy, balanced diet that’s low in saturated fat is key.” This means prioritizing fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats found in olive oil, nuts, and avocados, rather than fixating on the cholesterol number of a single food item.

USDA Issues Nationwide Health Alert for Frozen Pasta Over Undeclared, Life-Threatening Allergen