Beyond the Tap: Are Special Washes Needed for Cleaning Vegetables Safely?

Experts weigh in on the best methods for cleaning vegetables, analyzing the science behind using plain water, vinegar, and baking soda. While the FDA recommends cool running water, studies show baking soda can effectively reduce surface pesticide residue.

Amid growing consumer awareness of food safety, the simple act of cleaning vegetables has become a subject of intense debate, pitting traditional home remedies against scientific guidance. While federal health agencies maintain that cool running water is sufficient for most produce, studies exploring household staples like baking soda and vinegar have added nuance to the discussion, leaving many to wonder which method is truly most effective at removing contaminants like pesticide residue and harmful bacteria.

This ongoing conversation highlights a fundamental question for kitchens worldwide: what is the best practice to wash produce before it reaches the table? Experts say the answer depends on balancing practicality with scientific evidence.

The Debate Over Cleaning Vegetables: What Does the Science Say?

For years, the official guidance from public health bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been consistent and clear. Both organizations recommend simply rinsing fresh produce under cool, running tap water and, for firm items like potatoes or melons, using a clean vegetable brush to scrub the surface.

“For the vast majority of consumers, plain running water is a safe and effective way to remove most surface contaminants,” said Dr. Amanda Deering, an Extension Specialist in food safety at Purdue University. “The mechanical action of rubbing or scrubbing the produce under water is critical for dislodging dirt, debris, and some microbes.”

The FDA explicitly advises against washing fruits and vegetables with soap or detergents, as these products are not intended for consumption and their residues can be absorbed by porous produce. The agency also states that commercial produce washes have not been found to be any more effective than water.

Evaluating Common Household Methods

Despite official guidance, many continue to use additives like baking soda or vinegar, citing anecdotal evidence and family traditions. Recent scientific inquiry has begun to test the efficacy of these “grandma’s tricks,” with some surprising results.

The Baking Soda Solution

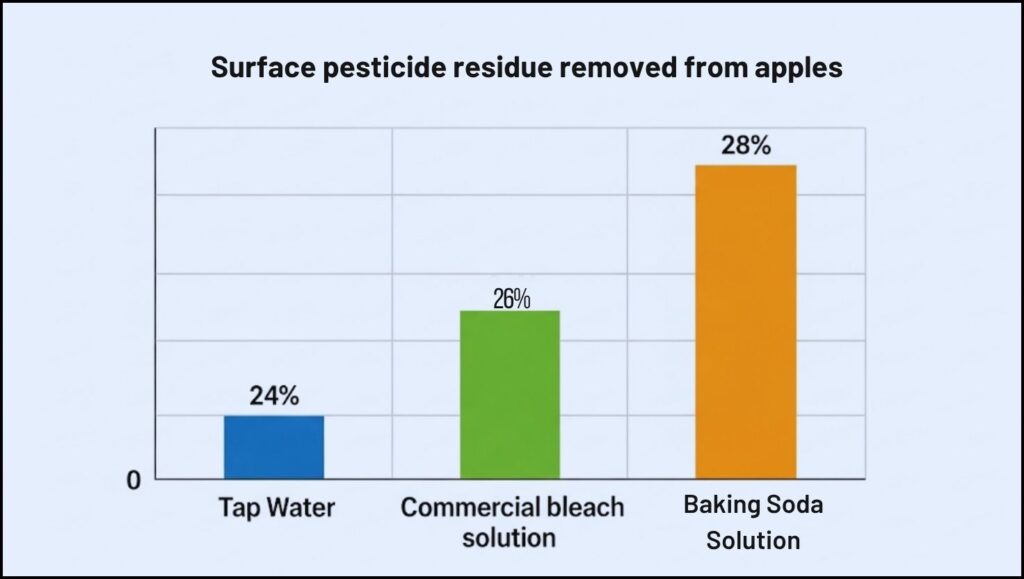

A notable 2017 study from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, brought significant attention to baking soda (sodium bicarbonate). Researchers applied two common pesticides—thiabendazole and phosmet—to organic apples and then washed them using three different methods: tap water, a 1% baking soda solution, and a commercial bleach solution approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The study found that soaking the apples in the baking soda solution for 12 to 15 minutes was the most effective method, removing 80% of the thiabendazole and 96% of the phosmet. “The alkaline nature of baking soda can help degrade certain types of pesticides, making them easier to wash away,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Lili He, explained in a university release. However, she cautioned that the method might not be as effective for pesticides that have penetrated deeper into the peel.

The Vinegar Rinse

Vinegar, an acetic acid solution, is often touted for its antimicrobial properties. Research has shown that a soak in a diluted vinegar solution can significantly reduce the bacterial load on produce. One study published in the journal Food Control found that a vinegar solution could reduce Salmonella on lettuce and tomatoes.

However, experts note that vinegar is not a cure-all. It is most effective against certain bacteria and less so against viruses. Furthermore, a high concentration can negatively affect the taste and texture of more delicate items like leafy greens or berries. “Vinegar can be a useful tool, but it’s not strictly necessary for safety if you are properly washing with water,” Dr. Deering noted.

The Real Risks: Pathogens and Pesticide Residue

The primary concerns driving washing habits are microbial pathogens and pesticide residue. While the U.S. food supply is among the safest in the world, foodborne illness outbreaks linked to contaminated produce, such as E. coli in romaine lettuce or Salmonella in cantaloupe, do occur. The Environmental Working Group (EWG), a U.S. activist group, annually releases its “Dirty Dozen” and “Clean Fifteen” lists, highlighting produce with the highest and lowest levels of pesticide residue. While the list raises consumer awareness, many toxicologists and food scientists point out a critical piece of context.

“The levels of pesticides detected on produce are nearly always well below the tolerance limits set by the EPA, which are established with a large margin of safety,” said Dr. Carl Winter, a retired cooperative extension specialist in food toxicology at the University of California, Davis. A 2011 study he co-authored found that substituting organic forms for the “Dirty Dozen” items did not result in any appreciable reduction in consumer risk.

Ultimately, federal agencies and food scientists agree that the health benefits of a diet rich in fruits and vegetables far outweigh the potential risks from pesticides or bacteria. The consensus remains that the most important step for public health is ensuring produce is washed at all. A thorough rinse under cool running water remains the gold standard for food safety at home. While methods like a baking soda soak may offer additional benefits for removing certain surface pesticides, they are not a substitute for the fundamental practice of washing.

The Parasitic Risk Fueling Warnings Against Eating Unwashed Berries